Source: Al-Wafd Newspaper

Prof. Dr. Ali Mohammed Al-Khouri

At the heart of the biological revolution that is reshaping our understanding of health, identity, and human history, the Arab world remains largely absent from the stage of major scientific events, particularly in the field of human genomics, which has become the backbone of precision medicine, proactive diagnosis, and the development of food security strategies. The challenge lies not in the weak Arab presence within this field, but rather in the lack of a strategic vision that treats genomic research as a tool of sovereign knowledge, not merely as an academic project detached from development paths and political decision-making.

Arab scientific research is experiencing a chronic structural decline characterized by insufficient investment, fragmented institutional frameworks, and a lack of effective political will. While developed countries allocate between 3% and 4% of their GDP to scientific research, most Arab countries spend less than 1%, with some not even exceeding 0.2%. This disparity translates not only into a gap in the number of published studies and research papers but also into a near-total absence from international scientific decision-making bodies, where the genetic future of humanity is being mapped out.

The importance of the Arab genome lies in its role as a vital repository of knowledge for understanding the region’s diseases, genetic history, and population diversity. Furthermore, it offers invaluable tools for developing healthcare systems and enabling local agriculture to meet climate and production challenges. Studying the Arab genome has become a strategic imperative for the region’s biosecurity, its capacity for knowledge production, and its ability to localize health and food solutions.

Despite its importance, the Arab contribution to global genomic research remains minimal, if not nonexistent. Studies indicate that Arab representation in major genomic projects in no way reflects the region’s demographic, cultural, and environmental weight. The rich genetic diversity of Arab societies, a result of historical interactions between Asia, Africa, and Europe, is not being utilized in international laboratories or documented in global databases. This absence not only deprives the region of future participation but also excludes it from shaping the scientific standards that will frame medicine and health policies for decades to come.

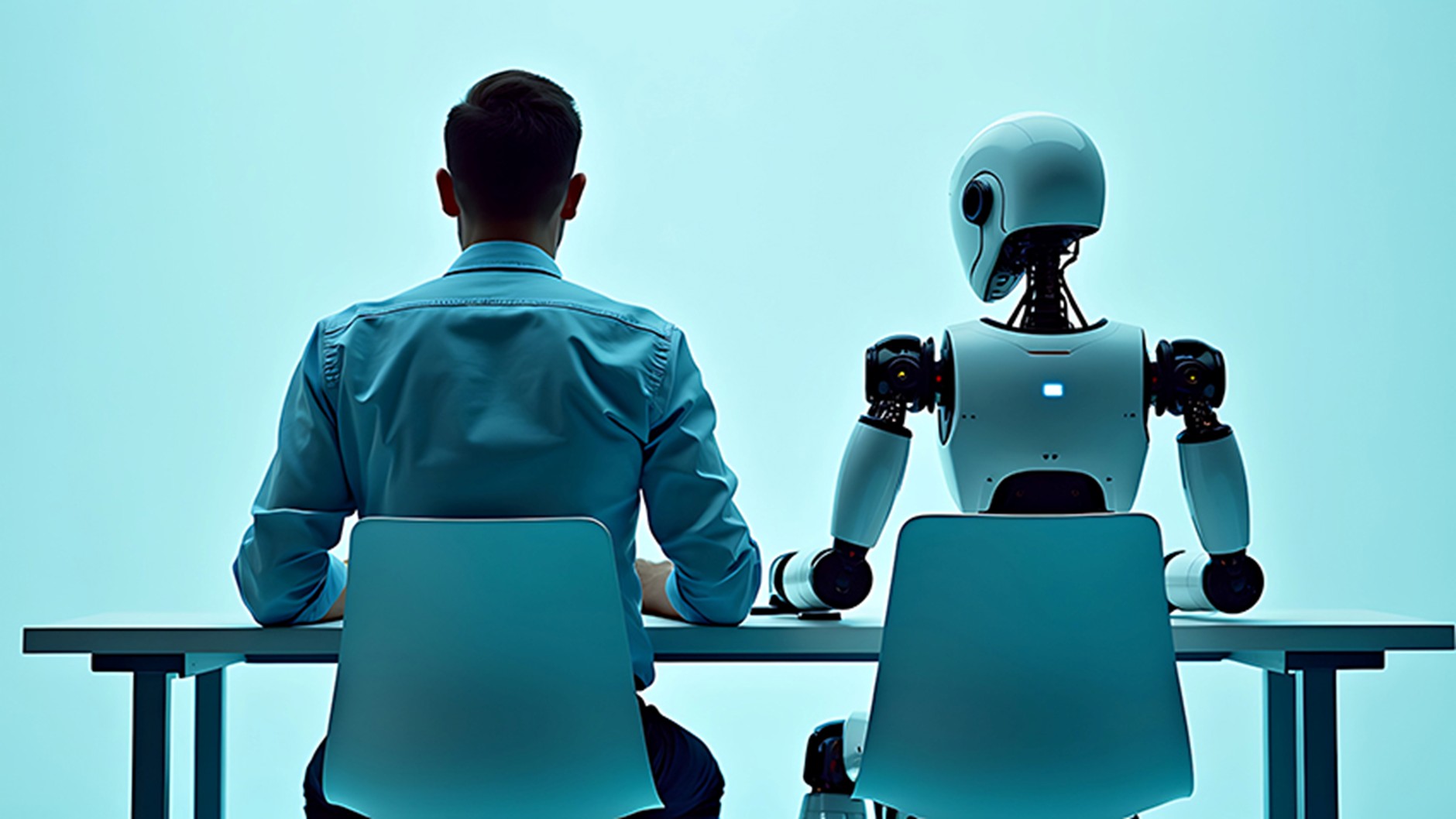

The crisis deepens when we consider the strained relationship between scientific research and emigration. Many Arab scientists seek to pursue their research careers in scientific environments that offer more favorable conditions in terms of institutional support, infrastructure, and freedom of scientific exploration. Their decision to work abroad is often driven by a desire to develop their projects within mature research systems that allow them to reach their full potential—something that remains a challenge in many scientific institutions in the Arab region.

The cruel irony is that the Arab researcher becomes an active participant when he leaves his homeland, and absent when he returns. Herein lies the danger: not only in the brain drain, but also in the loss of connection between global scientific centers and the societies that produced these minds in the first place.

What further complicates the situation is the Arab world’s lack of a comprehensive research policy that fosters an institutional scientific environment, provides equitable conditions for academic excellence, and transforms knowledge into a strategic imperative. Universities often operate in isolation, research centers lack funding and independence, and international cooperation rarely extends beyond formal conferences or agreements of intent.

However, there are promising signs, albeit limited, suggesting the possibility of a nucleus forming for coordinated Arab action in the field of genomic research. The Qatar Genome Project is one such ambitious initiative aimed at building a genetic database of the population, which can be used to develop precision medicine applications in a scientific and systematic manner.

In Egypt, the National Human Genome Project is progressing promisingly, although it is contingent on overcoming complex logistical and organizational challenges. However, it has the potential to become an effective model for linking genetic knowledge with national health needs.

In addition, the UAE Genome Project represents a highly significant experience, not only because of its ambitious scale, which aims to collect and analyze one million genetic samples, but also because of its comprehensive vision that links biological knowledge with investment in preventive health, based on an advanced infrastructure and a clear national strategy.

These initiatives, despite their geographical distance and varying capabilities, collectively constitute initial indicators of the possibility of forming a vital scientific bloc that deals with the Arab genome as an integrated sovereign file, not a passing academic topic.

In light of this reality, a renaissance in Arab genomics cannot be discussed without a genuine re-establishment of the concept of scientific research in the region. This requires a political will that considers knowledge an integral part of national security, and a long-term investment whose results are not measured by narrow, short-sighted investment calculations, but rather by the state’s capacity for resilience, innovation, and achieving knowledge sovereignty.

What we must consider deeply is: why don’t we treat the genome as a dimension of Arab identity? And why isn’t genetic diversity viewed as a strategic asset upon which to build an independent scientific discourse? What we lack today is not merely funding or infrastructure, but a vision that transforms us from consumers of genetic information to producers of biological knowledge. When this happens, the Arab genome will not be just a scientific project, but a new horizon for redefining our relationship with the world and with ourselves.

At a moment when the world is rushing towards a bio-knowledge economy, where genetic information is becoming a strategic commodity, our absence from the scene is not just a shortcoming, but a silent threat to our future health, and our alienation from one of the most important fields that will determine the shape of the world to come.